“Jettisoned from vision and representations via legal prohibitions and related forms of censorship, violence is thus shaped by a notion of un-representability that is deployed by at the same time that it serves the very forces that inflict it” ~Elizabeth Adan (Seeing Things)

I performed an hour long performative lecture here at Flower City Arts Center a couple of weeks ago and I was amazed by the turn out! Thank you to everyone who came to see the performance and discuss the project afterwards. Rochester’s interest and support in my current work: “Luz del Día: Copyrighting the Light of Day” continually surprises me.

The performance reflected on my inner conflict about representing and historicizing violence that is difficult to imagine or reconcile within oneself. I lead the audience through four exercises while simultaneously blending installation, political documents, the archive, and the illusive nature of the documentary image and missing national history.

For the performance’s first phase, I asked the audience to turn their chairs towards me and away from the projected screen and to close their eyes. I then played a sound recording of the gentle whispering of women whose voices could barely be understood. Those in the audience who understand Spanish made out that the woman was stuck in a box. As the recording continued, I have overlayed the sound so that the quiet whispering became more intense and layered, although still quite low in volume. The sound recording is from the El Archivo General de La Nacion de Argentina and is from the dictatorship.

The reaction of audience members varied. Some audience members became agitated as they were seemingly unable to respond or did not know how to do so. Others expressed frustration afterwards because they didn’t understand the content of the recording and why it was being played. Still others had related mental impressions of the sounds that they experienced as they allowed the whispering to make their minds imagine.

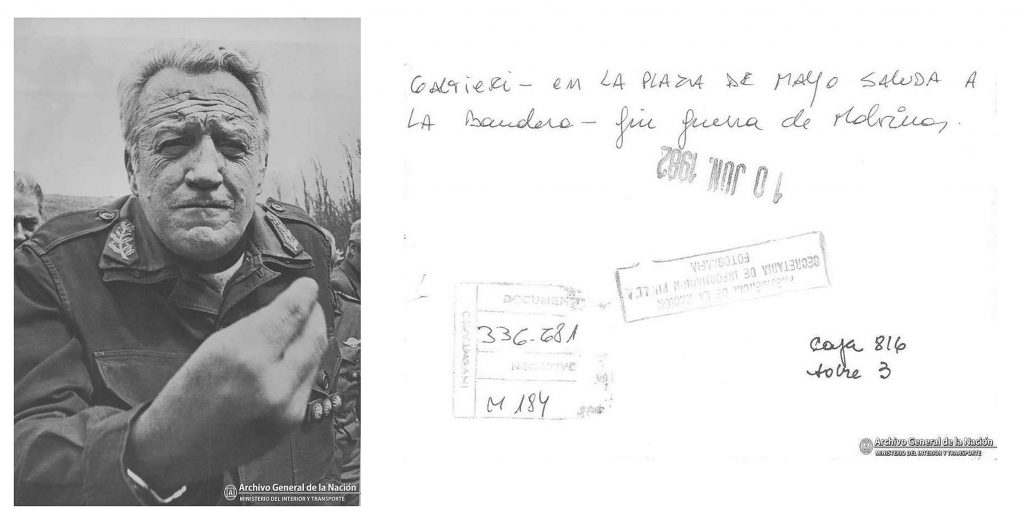

For the second phase, I asked the audience to open their eyes, and turn their heads to view the projected image but not their bodies to face it. This puts them in the physical posture of “looking”, with its accompanying distancing and potential physical discomfort. They then saw the image displayed via an overhead projector. Scattered light boxes were installed on the floor in the performance space. These were covered with both my altered images from the Dirty War and CIA documents from that the Obama administration recently released, which reveal the United States’ support for the junta and its veiled encouragement for the Dirty War.

Several aspects of this phase reinforced the motif of accessibility/inaccessibility that permeates the full performance. The documents are written in a mixture of English and Spanish, so are unreadable to many (perhaps most) audience members. The document paper thrown seemingly haphazardly on the light boxes mute the light, but not consistently, creating areas of inconsistent shades of darkness and light. The projected image displays the shadow of my hands as I placed an altered image from the Dirty War printed on transparency paper onto the overhead project. I swiftly replaced one image with another, so that the image could only be glimpsed.

During this phase I spoke in Spanish, about my family’s experience of the war and those in my family whom the state murdered. I spoke of the images that I place onto the projector, the role of copyright law in national memory, and how to reconcile violence that left little physical remnants.

I then began the third phase of the performance: I overlaid the images on the projector until the images were obscured, so that both it and the room were dark. Speaking in English, I tell the story of Argentinian Copyright Law, Copyright Law in relation to orphaned images, and the current status of Proposed Bill No.2517-D-2015. I also started to remove the images from the projector, so that light returned to the room and the images become visible. Once I removed all of the images, I place them back on the projector and repeat the process.

At first, this portion of the performance exudes quiet and calm both in my voice and in the manner I remove the images. But as it continues, my voice becomes louder, faster, and more intense, and the rate at which I place and remove images on the projector faster, and potentially violent. At that point that this energy climaxed, and I began the last and final phase of the performance. I turned off the overhead projector and ask the audience again to turn back to the front, and close their eyes. I then replayed the same sound recording I played during the performance’s first phase. Partway through the recording, I leave the performance space so that the audience can decide how they want to end the performance.

Thank you so much to Flower City Arts Center volunteer Mike Buongiorne for helping me document this performance! The last few images are of a video I am editing that will walk the viewer through the performance. I am currently at Bard College Library surrounded by a pile of books on the Argentine Dirty War to continue the research portion of this project. I will be lecturing at the University of Rochester’s History Department this Thursday and RIT’s Art Department this Friday.

“The unrepresentable ‘runs a twofold risk’ to subtract it, in the name of its exceptionality from ordinary conditions of representation is dangerous as making it commonplace by representation is as dangerous as making it commonplace by representing it according to the same rules as others…It is through the imposition of presence that art can explore phenomena such as mass violence…what is to be presented is not the executioners or the victims but the process of double elimination: of the traces.” (Ranciére)

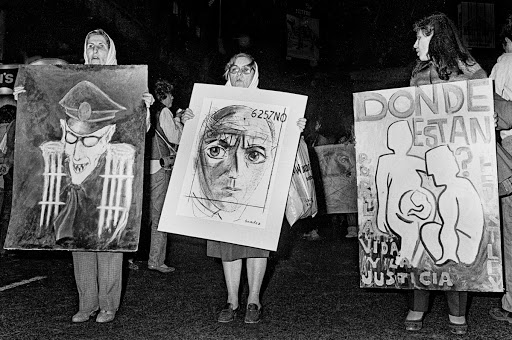

Abuelas de plaza de mayo, mothers who turned into grandmothers protesting the disappearances of their sons and daughters take to the streets armed with Argentinian paintings. (Image: Mónica Hasenberg)

Abuelas de plaza de mayo, mothers who turned into grandmothers protesting the disappearances of their sons and daughters take to the streets armed with Argentinian paintings. (Image: Mónica Hasenberg)